Exercise 1

A. Listen. What do Edgar and Ariya talk about?

B. Listen again. Answer the questions.

1 Why is Edgar upset?

2 What are adulting classes? What are some likely subjects?

3 What does Edgar claim are the stereotypes? How does both he and Ariya refute them?

Answers

A

millennial stereotypes

B

Possible answers:

1 He believes the media unfairly presents all millennials in the same (stereotypical) way.

2 They are classes offered to people who feel they lack basic life skills. Some examples are cooking, budgeting, time management, home improvement, etc

3

Stereotype 1: Millennials are narcissistic, immature, unreliable, lazy, and selfish.

Arguments: Ariya and Edgar both feel that these characteristics are untrue and are perpetuated by the media. They feel that they work hard but know the importance of work-life balance.

Stereotype 2: Millennials need to take cooking classes.

Arguments: Edgar believes that learning how to cook does not automatically make you an adult. Ariya feels that she’s too busy and prefers the faster method of ordering takeout in order to spend more time with her family.

Stereotype 3: Millennials need to take home repair classes.

Arguments: Edgar disagrees and would rather spend his free time relaxing and enjoying life. Ariya also disagrees and points out that not everyone owns their own home.

Stereotype 4: Millennials can’t save money to buy a home.

Arguments: Edgar and Ariya believe that this statement is absurd. They spend money responsibly.

Stereotype 5: Millennials don’t get married and don’t have children or pets.

Arguments: Edgar believes that this is a ridiculous stereotype, pointing out (in a humorous way) that Ariya has done all of these things.

Audioscripts

Edgar: I’m so tired of stereotypes about millennials! We’re characterized as narcissistic, immature, unreliable, and selfish.

Ariya: OK.

Edgar: These generalizations are so unfair. Why do they always have to sensationalize absolutely everything?

Ariya: By “they” you mean the media, right?

Edgar: Yes. The ideas that millennials are lazy and that we refuse to grow up are perpetuated by articles like this.

Ariya: So, you’re reading the article about adulting classes, huh? My sister told me all about it.

Edgar: You mean another article about learning how to be an adult. There are millions and millions of them. This one focuses on the assumption that millennials need to take cooking classes. Like knowing how to cook makes you an adult.

Ariya: I don’t cook. Let’s look at this objectively. I’m too busy. It’s much faster to order ahead and have a delicious meal with my family from one of our favorite restaurants.

Edgar: I agree with you a thousand percent. And I don’t need to take an adulting class on how to do home repairs either. I would rather spend my free time relaxing and enjoying life. We millennials aren’t lazy. We have the right mindset. We work hard, but we know the importance of work-life balance.

Ariya: Right! Plus, you rent an apartment! You don’t even own a home.

Edgar: Oh, that reminds me of another point. The idea that millennials can’t save money to buy a home because we spend too much money on avocado toast and gourmet coffee is absurd.

Ariya: I know. Admittedly though, I do love avocado toast, and it’s not that expensive. And I know you love it, too. In fact, didn’t you post a photo of your breakfast this morning?

Edgar: Yes, I did.

Ariya: What a millennial thing to do! By the way, I love the new selfie of you and your dog.

Edgar: Ah, yes, my “son.” My mother complains about the fact that I would rather have pets than children.

Ariya: I think that’s part of the generation gap. My husband and I had a similar experience with my mother before our son was born. She really wanted a grandchild.

Edgar: Ooh! Wait! I just realized. A major stereotype has been shattered! You’re a millennial who is truly an adult. You’re married, with a son—and a dog!

Ariya: OK, OK. But I’m still not a homeowner…yet.

Exercise 2

A. Listen. What is the topic of the podcast?

B. Listen again for phrases that guide a conversation. Write the name of the speaker.

1 Let’s start off with … ________

2 We’ll come back to that later. ________

3 Moving on, … ________

4 And on a related note, … ________

C. Listen again. Take notes in the chart.

|

Field of science |

What science says |

|

Psychology |

|

|

Sociology |

|

|

Physiology |

|

Answers

A

Possible answer: the science behind being a sports fan

B

1 Mickey 2 AJ 3 Mickey 4 AJ

C

|

Field of science |

What science says |

|

Psychology |

Fans are happier about their own lives when they’re cheering for their favorite teams. Because fans identify with teams, they have higher self-esteem. Being a fan is similar to being in love. Humans don’t distinguish between themselves and those they love. Fans don’t want to lose a part of themselves, so they remain with their team whether the team is winning or losing. |

|

Sociology |

Humans have an inclination toward being in groups. The camaraderie between fans of the same team helps fans feel less depression, alienation, and loneliness. |

|

Physiology |

Because of what happens in the brain, fans have a rush of adrenaline, a faster heartbeat, and faster breathing. Mirror neurons in the brain make fans feel like a member of their favorite team. |

Audioscripts

A: Hey, sports fans, I’m Mickey Owen and this is Mickey’s Mic. My guest today is sports psychologist AJ Paluch. AJ‘s most recent work is about the science behind sports fandom. Thanks for being here, AJ.

B: Thanks for having me.

A: AJ, like most fans, I believe the connection I have with my favorite teams is visceral. I don’t analyze it. I just feel it. But you say there’s science behind sports fandom.

B: That’s right. Sports scientists have done some telling research that involves three fields of study— psychology, sociology, and physiology.

A: Let’s start off with psychology.

B: Simply put, being a sports fan helps people feel better. Psychologists use terms like “cathartic healing” to explain that fans are happier about their own lives when they’re cheering for their favorite teams. When their teams succeed, they share the success. They have higher self-esteem.

A: So, fans are living vicariously through their teams?

B: We’ll come back to that later. I’d like to talk about relationships first. Researchers have made correlations between how sports fans feel about their teams and how the human brain perceives relationships. When humans are in love, they have trouble distinguishing between themselves and the person they’re in love with. And they stay with that person through good and bad.

A: OK.

B: The same goes for sports fans. They stick with their teams even when they lose. Abandoning the team would be like losing a part of themselves.

A: I know about that. I waited forever for my team to win a championship! Moving on, what about the sociology of sports fandom?

B: Humans have a natural inclination toward belonging to a group. Millions of years ago, group membership was necessary for the survival of our ancestors. Today, we still want that sense of belonging. Research shows that the bond between fans results in less depression, less alienation, and less loneliness.

A: Watching a sporting event does build camaraderie.

B: Yes, and think about it. There can be thousands of spectators at a game who are total strangers. But because they’re wearing the same team colors and cheering in unison, they’re all members of the group.

A: They’re all experiencing the excitement of the moment, too. Watching sports sure gets your heart racing.

B: That’s part of the physiology of being a sports fan. Fans have a rush of adrenaline, a faster heartbeat, and a higher rate of respiration as a result of what happens in our brain while watching sports. And on a related note, there are mirror neurons.

A: Excuse me?

B: Mirror neurons are brain cells that function when we’re performing an action or just watching it. They make spectators react as if they were actually athletes playing in a competition. Earlier you asked if avid sports fans live vicariously through their teams. Mirror neurons help explain the reason why fans say things like “we won” and why they identify so strongly with a team.

A: Amazing! This has been a very interesting conversation about why so many of us are hooked on sports. Thanks again, AJ.

B: My pleasure.

Exercise 3

A. Listen. What is the speaker’s main message?

B. Listen again. Take notes on the three areas of bias.

|

Type of bias |

Description / Examples |

|

Bias in the machine |

|

|

Bias in society |

|

|

Bias in the brain |

|

C. The speaker is trying to persuade the audience that social media is biased. Which persuasive techniques does he use?

Answers

A

Possible answer: The speaker wants to raise awareness of bias on social media.

B

|

Type of bias |

Description / Examples |

|

Bias in the machine |

Social media content is determined by algorithms; algorithms filter the content we want/don’t want to see, meaning we typically view content that confirms our own beliefs |

|

Bias in society |

We surround ourselves with people who share our views; we might experience an echo chamber, where our own beliefs are echoed by friends on social networks |

|

Bias in the brain |

Our brain uses some tricks to decide which information is worth sharing; our brain prioritizes negative information due to its potential risk; news companies make headlines negative to encourage us to read them; Dunning-Kruger effect, the less we know about a topic the quicker we are to believe what we read about it |

C

Possible answers: The speaker uses rhetorical questions to encourage the audience to connect emotionally with the talk; The speaker directly addresses the audience to personalize the talk; The speaker adopts an informal style at times to associate with the audience; The speaker uses the “rule of three” to list the points of the argument emphatically.

Audioscripts

Bias in the News

OK, today I’m going to talk about the news. But before I do, I have some questions for you.

Where do you get your news? And how does that source decide which news to show you? How do you decide that the source is worth viewing? You’re in control of that decision…aren’t you?

I’ll bet a lot of you get your news from social media. Well, consider this well-known fact: social media is plagued with bias and misinformation. It is vulnerable to it. In fact, studies have shown that false information outperforms true information on social media, and that nearly a quarter of U.S. adults have shared fake news with friends—whether they knew it or not. Fake news can be hard to recognize, so it’s important to fact check news articles before you share them.

Then there’s the problem of bias in the news, which can be even harder to identify because the information in the articles may be factually accurate. Let’s examine this issue more closely.

Researchers from Indiana University have identified three main types of bias that particularly plague social media. The first, which may sound familiar, is “bias in the machine.” Social media content is determined by algorithms, which are basically a set of guidelines that determine what we see. These guidelines are informed by our own activity. If we often click on links that take us to particular news sites, algorithms make sure this type of content appears more frequently in our news feeds.

Algorithms also filter content that we don’t want to see, such as, say, different opinions to our own! We exist in a filter bubble, where content is comfortable, and it usually serves to reinforce our own beliefs. Algorithms work across all platforms, so there’s no escaping them.

The second well-known bias is “bias in society.” We tend to surround ourselves with people who share similar beliefs and views. On social media, we are likely to share content from our social circle, as, again, it usually reinforces our own beliefs. Other friends will then look favorably at the content we shared, and do the same. Eventually, we end up with what’s called an echo chamber—the same views and beliefs are repeated, and there is little room for alternatives.

So, we can’t trust the system to share balanced content; and we can’t trust other people like our friends. Surely, we can at least trust ourselves, right? Unfortunately, not, because the third bias is actually “bias in the brain.”

We encounter tons of information every day—there’s no way that we can pay attention to all of it—so our brains use a number of tricks when deciding which information is worth reading or sharing.

One of these tricks is to view emotionally-driven content, especially negative content, as shareworthy. Why? Well, it is believed that this is an evolutionary trait. The brain naturally prioritizes negative information over positive, as the potential threat that negative information might cause is higher. A research team from the University of Denmark found that this brain bias is being exploited by information sharing sites. News content with a negative headline is more likely to be shared.

Another one of our brains’ shortcuts plays on our ignorance. Basically, the less we know about a topic, the quicker we are to believe what we read about it. Let’s say you read a headline that says, “carrot juice helps cure cancer”. You know very little about the health benefits of carrot juice, and you’re pretty sure that there isn’t yet a cure for cancer. However, because you know so little about the topic, you might actually be swayed into believing some of what you read.

So, there you have it. Bias is everywhere on social media. It’s inherent in the system, and in ourselves. It benefits from our desire to make “being informed” less effortful, and our tendency to stick with what we know. But if we really want to be informed, it’s important to think critically about what we read, and to seek out different sources for our news.

After all, we may find comfort among those who agree with us, but we experience growth among those who don’t.

Exercise 4

A. Listen to the article. Explain the title.

B. Listen again. Answer the questions, according to the article.

1 How have our friendships changed since the arrival of social media?

2 What is the relationship between online friendships and well-being?

3 What is meant by emotional distance, and how does it affect friendships?

4 What overall impact does the lack of intimacy have on our online relationships?

Answers

A

Possible answer: The writer feels they are worse, for the time being at least.

B

1 We now have more friendships, although these normally amount to casual friendships. The closeness quality of friendships hasn’t changed. We still have the same number of close / intimate friends.

2 Online friendships do not seem to affect our happiness or well-being, as opposed to real-world friendships.

3 Emotional distance is the depth of connection you have with somebody on an emotional level. Physical contact, such as hugging, is an indicator of your emotional distance to somebody. Research suggest that physical touch is important for building bonds.

4 The overall impact is that most online friendships remain casual and don’t develop in intimacy. They don’t satisfy us—not in the same way that real friendships do. They seem to have no effect on our happiness.

Audioscripts

MODERN FRIENDSHIPS: IS MORE REALLY BETTER?

BY KERRY M. KENDRICK

In the 1990s—the pre-social networking era—anthropologist Robin Dunbar estimated that the average person can maintain around 150 friendships. This figure, also known as “Dunbar’s number,” has been popularized since then, appearing in books and articles.

What has happened to this number since the advent of social media? While it is estimated that the average social media user has 150 friends, it is also estimated that the average person has seven social media accounts. Friendships these days are not restricted to real-life interactions, nor are they restricted to one social media platform. So Dunbar’s number might sound like a drop in the ocean to social media users who have friend counts in the thousands.

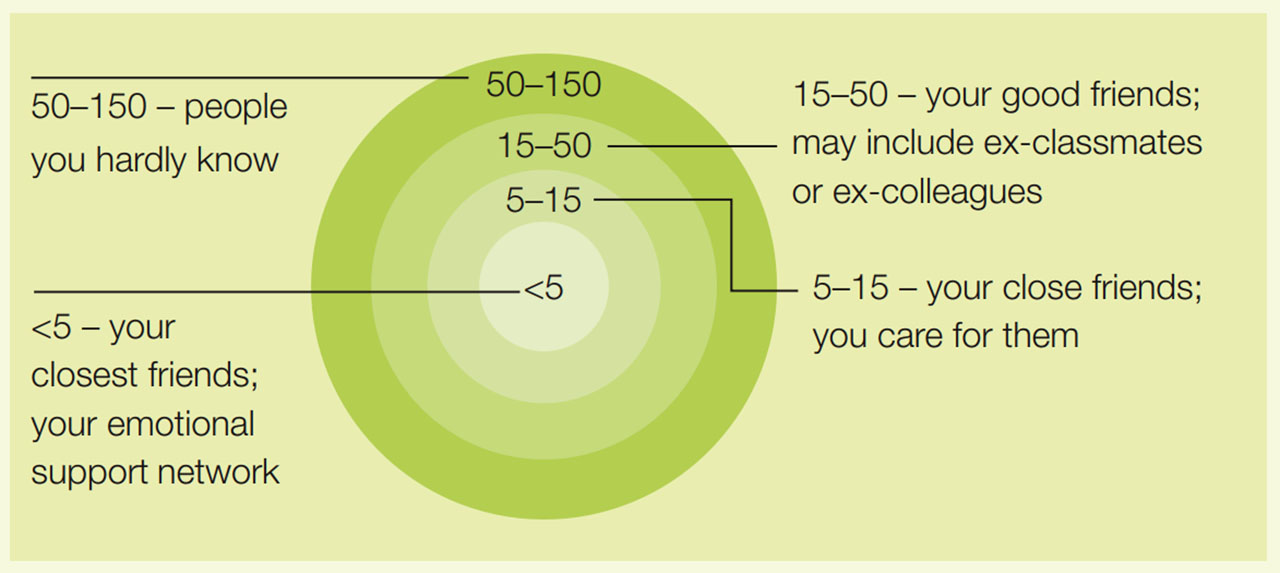

But evidence suggests that quantity doesn’t necessarily mean quality. In Dunbar’s initial research, friendships were broken down into types. The average person had around fifty good friendships, fifteen close friendships, and an intimate support group that usually consisted of just five people. Current research has shown that although our average number of total friendships has increased, the number of close and intimate friendships we maintain has stayed roughly the same. We may acquire more online friends, but a majority of these will probably be casual acquaintances. Online friendships may be commonplace, but research suggests they are no substitute for the real thing.

Why don’t the online friendships we build become more intimate? It’s possible they don’t satisfy us—not in the same way that real friendships do. Researchers found that our number of real-life friends directly correlates with our well-being—the more friends you have in real life, the happier you are. However, they found no evidence that the size of our online friendships has the same effect. Even if our virtual friendship network grows far beyond Dunbar’s number, it’s still our real-life friendships that mean the most to us. The underlying issue making these virtual relationships seem less fulfilling could be emotional distance. Researchers found that people are happier and laugh 50% more frequently during face-to-face interactions as compared to online interactions. The emotional touch of face-to-face interaction, such as responses like genuine laughter, is very important. Further research has shown that physical touch, like hugging, is also crucial for building social bonds. Video calls can bridge the gap to an extent, but it isn’t possible to fully replicate physical bonding in a virtual world.

Overall, research suggests that online relationships can’t fully meet the social and emotional needs of most adults. They fail to reproduce the emotional and physical intimacy of real-life friendships, and they don’t trigger the same feelings of well-being as real-world relationships do. Social networks may evolve to accommodate our relationship needs, but for now they are inadequate. Social media isn’t the place for close friendships; the real world is.

Exercise 5

Listen. Circle the correct answers.

1 The stadium doesn’t make / let / require people bring food to the games.

2 Her roommate helped / made / let her watch the soccer games.

3 They can help / have / let their neighbor record the game for them.

4 Their manager lets / makes / helps them participate in team-building exercises.

5 The doctor is helping / allowing / requiring Caleb to follow a diet.

6 Amir had / made / let his favorite baseball player sign his ticket.

7 Pete may be able to get / help / allow them in the stadium.

8 The swim team is required / getting / allowed in the pool.

Answers

1 let 2 made 3 have 4 makes

5 requiring 6 had 7 get 8 allowed

Audioscripts

1 We should grab something to eat before the game because the stadium won’t allow us to bring food inside. Do you want to go get some burgers?

2 I’m not a huge soccer fan, but my roommate forced me to watch every single game in the play-offs. I’ll admit they were pretty fun to watch.

3 We won’t get back from our trip until Sunday. It’s too bad we won’t be home to watch the tournament, but I’m sure our neighbor will record it for us if we ask him nicely.

4 I have a ton of work to finish up today, but our whole team has to play one of those “escape the room” games. Our manager insists that we do a bunch of team-building exercises to build camaraderie.

5 Thanks for ordering lunch. I hope you got some salads. Caleb can’t eat any gluten or dairy products right now because his doctor is making him follow a strict diet.

6 Don’t throw that old game ticket away! It’s not trash. Amir met his favorite baseball player after the game last week and asked him to autograph that ticket.

7 I really want to go to the game on Sunday but I think the tickets are sold out. Pete works at the stadium. Let’s see if he can get us in.

8 I really want to go for a swim but I’ll have to wait. Only the swim team is allowed in the pool right now.